As his career progresses, Hayao Miyazaki just keeps piling on the complexity of his films, and trying to see how many characters, plotlines and themes he can put in there and get himself out of it – and every time he manages to pull it off so effortlessly, he creates another masterpiece.

Like with Totoro, don’t even get me started on those ‘rumours’ about ‘what Spirited Away is really about’. Forget the weird commentaries, and focus instead on what Miyazaki always revolves his films around: coming of age, growing through adventure, learning the boon of collaboration with others, and hope for the future which today’s children can manifest.

In my newest video, I reveal:

- The specific reason why Hayao Miyazaki chose to make this film that reveals much about its story

- The Japanese Shinto background behind the film’s use of the water element

- Why the mystical bathhouse is a great analogy for growing up in traditional Japanese society

- How Chihiro’s personal development is about the Japanese system of ‘honne’ and ‘tatemae’

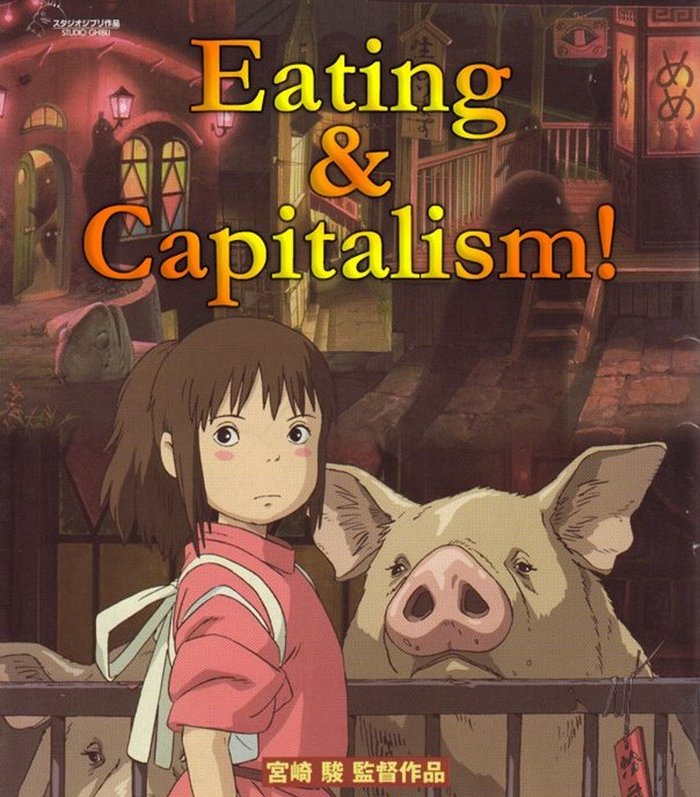

And I also talk about Miyazaki’s genius behind choosing the theme of eating to teach Japanese children about how capitalism works.

Sounds weird? Good. Prepare to see this film in a new light! 🙂

Watch the full video above, read the full transcript below, and don’t forget to grab your copy of the Studio Ghibli Secrets guide where I reveal the story patterns behind the multitude of Studio Ghibli films.

Get the Studio Ghibli Secrets Guide!

Spirited Away is really about growing up in modern Japan – full text

- Why Hayao Miyazaki chose to make Spirited Away

- The Shinto background of Spirited Away

- Bathhouses – an integral part of Japanese culture

- The bathhouse as social parallel

- ‘Spirited Away’ – what the title really means

- Chihiro and Sen – Japanese childhood vs. Japanese adulthood

- Spirited Away’s moral lesson – don’t get lost in your social facade

- The wider social context – Spirited Away and Japanese capitalism

- Eating as consumption in Spirited Away

- But Miyazaki’s not anti-capitalist

- So much more to discuss in Spirited Away…

- Now it’s your turn!

Hello everyone, quick show of hands, who’s seen this before? I will have to spoil the first ten minutes of the film, but the rest should be fine.

Hello and welcome to the third of our Summer of Ghibli original language specials here at the Duke of York’s, and today’s screening of Miyazaki’s groundbreaking work…

Eating and Capitalism.

(I promise that will make sense in a few minutes.)

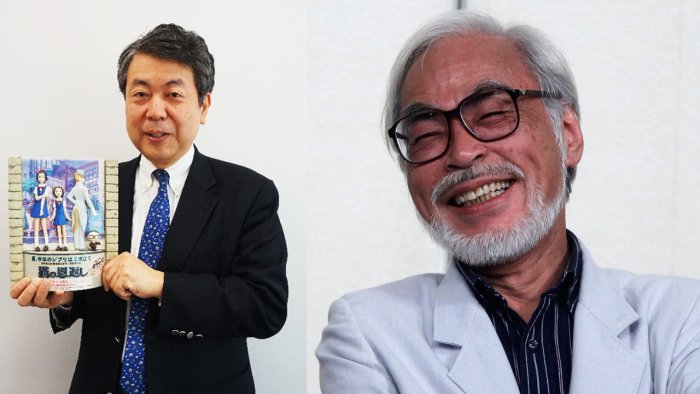

I’m Adam Dobay and I’m your host for this series. I have a background in film theory, storytelling and translation, I’ve researched Studio Ghibli for more than 7 years now and also lead the official translation to The Wind Rises.

Why Hayao Miyazaki chose to make Spirited Away

It’s safe to say that almost all Studio Ghibli films are deeply rooted in Japanese culture, folklore and mythology, and Spirited Away is even more densely packed than others. So I’ll be going into some of the elements that shaped this film and why they are important in understanding the story better.

So this film grew out of two separate things. One is a producer called Seiji Okuda, who started out as Studio Ghibli’s contact at NipponTV, but who became friends with Miyazaki over the years.

And one year in the late nineties, Miyazaki invited Okuda to bring his family to a holiday, to which Okuda brought his ten year-old daughter.

And as the families spent time together, Miyazaki realized that he had done films for 5 year olds and 7 year olds and 12 year olds, and 13 year olds and 14 year olds and 15 year olds, but not for ten year olds.

And he also looked into what was currently available for 10 year-old girls, like Ribon and Nakayoshi magazines, and saw that it’s mostly romance and Oh no, I’m having a fun and harmlesscrushon a slightly older boy, whatdo I do. And when talking to his producer friend’s daughter and other ten year-old girls, Miyazaki found that this is very far from what the actual concerns of ten year-olds are.

This is what I would call market research but what Miyazaki calls „paying attention to what children have to say when adults are actually listening”.

And so based on all these conversations, Miyazaki set out to create a character whose journey would answer the questions these young people were concerned about, and also someone who they could look up to.

The Shinto background of Spirited Away

So that is source #1 for the film, and source #2 was stumbling on a local Shinto religious festival by total accident.

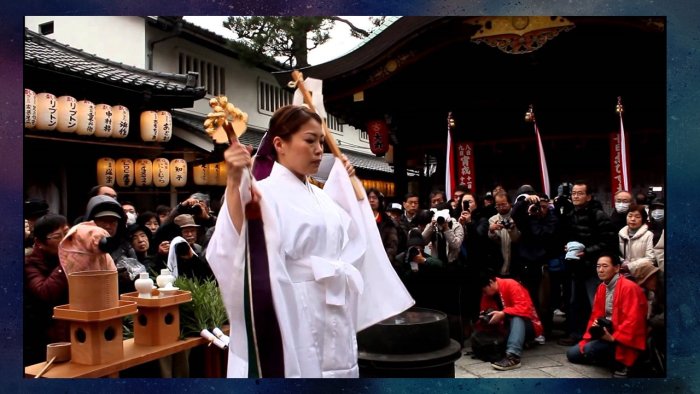

There are a lot of water purification ceremonies in Japan that are called Yudate, or “boiling water” rituals and some of them go back more than a thousand years. Here’s an example from Kyoto.

The basic format is that the priest or priestess specially prepares boiling water over an open fire and then they invite the gods in with ritual dances, so it becomes sacred water and sacred fire.

And then in the second part you sprinkle the hot water out on the audience for blessings and purification.

And you can tell which of the tourists and photographers actually read up about the ritual based on who runs away, who has a protective cover on their camera, and and who is the one lady out of the hundred people who actually participates in the ritual and actively receives the blessing.

Water as purification in Shinto

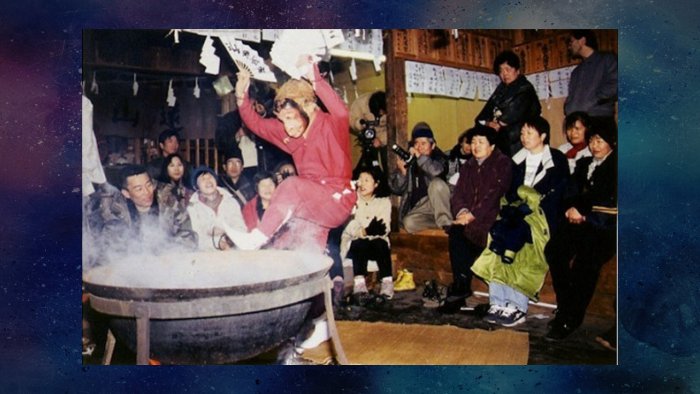

Now there are a number of variations to this winter purification ritual series, and one special type is the Shimotsuki Matsuri, “Eleventh Month Festival”, which refers to the winter solstice, a time of rebirth and initiation in most folklore systems.

And in one festival held in the Nagano mountain range, there’s a part where there’s a specific invitation for the gods to come into the water and enjoy a nice relaxing bath similar to how Japanese people enjoy nice relaxing baths around the country in hot springs.

And Miyazaki saw this ritual on TV and thought, Huh, this is interesting, why don’t we extend this concept to an entire bathhouse.

Bathhouses – an integral part of Japanese culture

So why a bathhouse? Bathhouses have a very long history in Japan, probably invented by the snow monkeys.

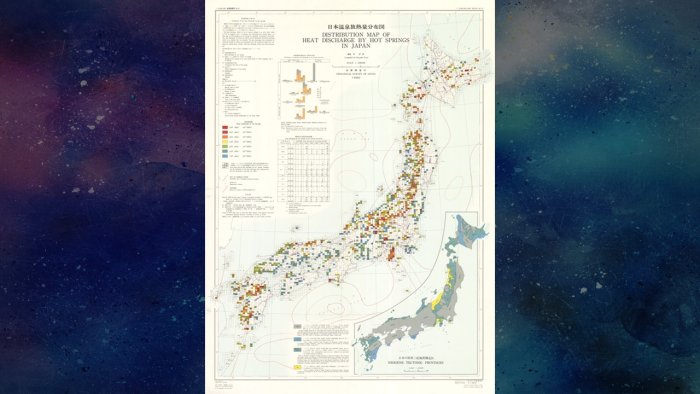

You can’t see it very well but every coloured dot on this map is a hot spring. There’s a total of 27 thousand hot springs all around the country, and a good 3 thousand onsen, or bathhouses built on them.

Public bathing is an integral part of Japanese culture, so much so, that before the modernization of Japan after World War II, most houses and even hotels didn’t come with a bath. You wanted a bath, you went to the bathhouse.

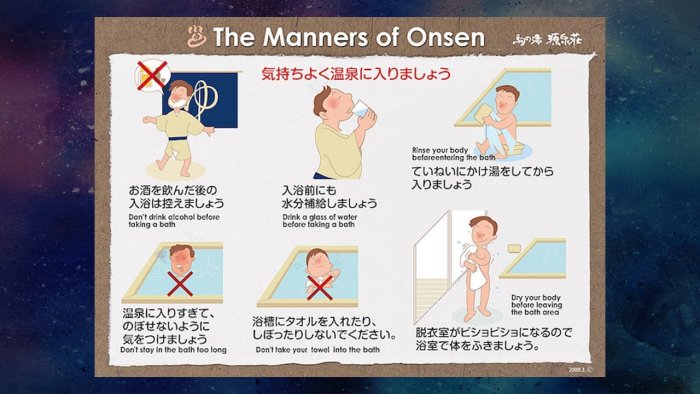

Also a difference from bathing in the West is how in Japan you first use running water to wash your body and only then do you take a bath, as you can see on this instructional poster.

While this system partly comes out of reasons of hygiene, it also gives a spiritual layer to taking a bath, as first you purify the body and then you relax and reconnect with nature and through that, purify the soul.

The bathhouse as social parallel

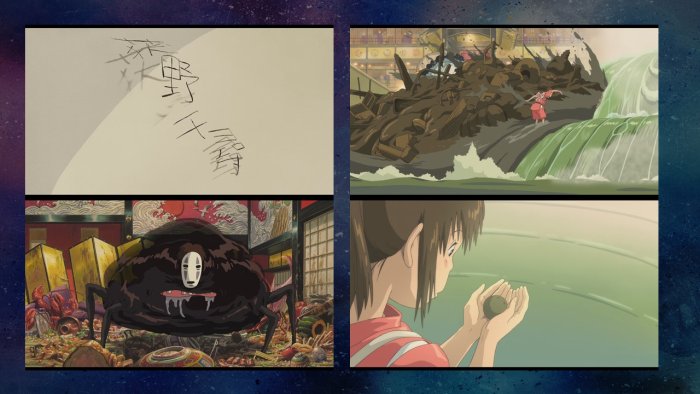

So for this film, Miyazaki who normally likes to focus on the wind element, explores the water element in its various meanings. So you can look out for all the ways water appears in this film and what it does.

Now bathhouses can be anything from basic facilities built over a hot spring, to these huge multi-level resorts, with hotels and restaurants.

And here’s the internal view of a more complex onsen as drawn by 19th century artist Utagawa Kunitoshi.

Of course this onsen is drawn with cats because everything is better with cats. So Miyazaki’s idea of an onsen for gods is not that far off, actually.

This layered structure and this ecosystem-within-a-building approach fits perfectly into the concept of using a bathhouse as a parallel for Japanese society while disguising the whole thing as a mystical adventure.

‘Spirited Away’ – what the title really means

And that’s where the title of the film comes in. Like with Princess Mononoke, the English title for this film sort of resembles the original title, but is just different enough to lose lot of the meaning.

I mean, “spirited away” on its own is fine, the original kamikakushi is a bit more nuanced, it means “a state of being hidden by the gods”.

Chihiro and Sen – Japanese childhood vs. Japanese adulthood

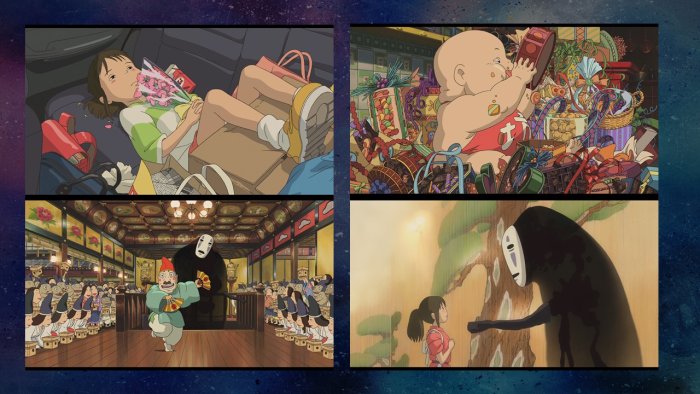

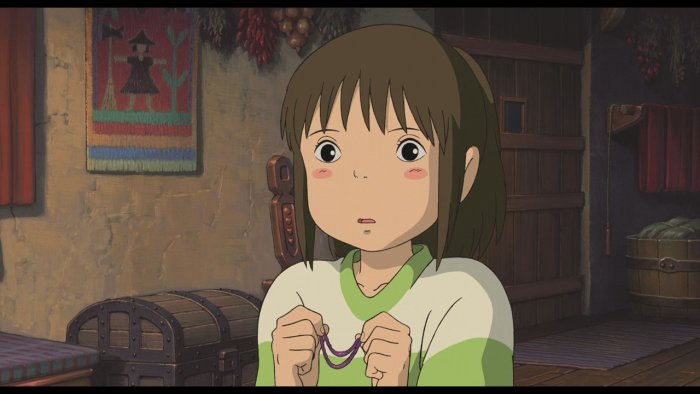

But the more important part is the two names. In the original Japanese, the title is Sen and Chihiro, hidden by the Gods. And that is kind of the point. You can get a very new reading of the film if you look at the relationship between the girl called Chihiro and the girl called Sen.

When you’re a child in Japan you exist as you are. It is your natural state, close to nature, even sacred. This is Mei from Totoro, quintessential Japanese child.

Learning the honne-tatemae system

And then you start to grow up and join Japanese society, and that is when you learn to operate on two levels, and separate your private self from your public self, your inward facing self from your outward facing self.

This is what is referred to as honne, literally „true sound”, which is your true feelings and desires. And tatemae, literally „built in front”, the mask you wear, your public behaviour based on what society expects you to do.

This means you have learn a whole set of social rules that dictate how you behave depending on context.

The way you speak, the way you present yourself to your peers, to your boss, the way you address those above and below you on the social ladder. Knowing these rules is the key to becoming a functioning adult in Japan.

Chihiro’s journey – relearning honne and tatemae

Now in the beginning of the film, Chihiro is absolutely horrible at observing and acting on Japanese social cues.

That is why in the first half of the film, she thinks there are two of people. But in most cases, there aren’t two of the same person, they are simply the public facing person and the private person.

As Chihiro gradually gets better at tatemae and learns to use it, that is what provides her breakthroughs throughout the film. She can look beyond the masks that people wear and reach out to the true self of the characters she meets.

Spirited Away’s moral lesson – don’t get lost in your social facade

But there’s another lesson here, about how easy it is to get lost in these social rules. You might learn and perform the tatemae perfectly, but forget your honne, your true feelings, hopes and dreams.

If the day-to-day life of adulthood grinds you down, your private self, your true self, is gradually lost. You become the role, you become the salaryman, the office lady, the father, the mother. You can perform the function but forget why you’re doing it in the first place.

And that is the real mastery of life, perfecting how to perform your Sen-ness, while holding on to your Chihiro-ness.

And that is why the other key to the film is remembering. It’s the simplest technique Miyazaki can give you. When in doubt, seek out your childhood self, because that is where your pure feelings are.

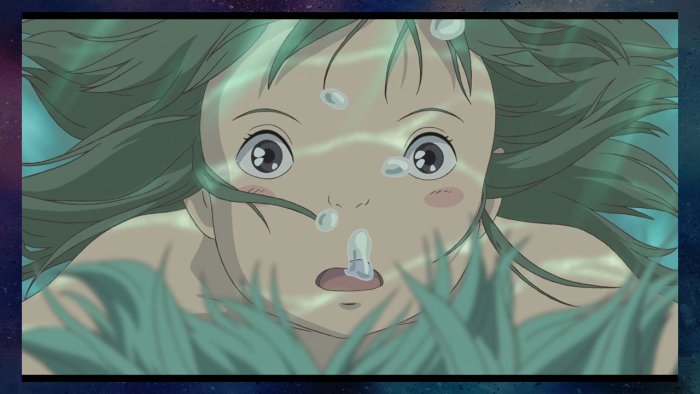

And how do you seek out your pure self? Get off all the muck that society and adulthood have put on you, and underneath you will find yourself.

The wider social context – Spirited Away and Japanese capitalism

That is the personal aspect of the film. The other aspect is the examination of our modern society at large.

So how does eating and capitalism factor into all of this? Well. First, there’s the parents. The parents represent 1980’s Japan, which built up this huge economic bubble over property and the stock market.

Spirited Away’s social context – the crash of the Japanese economic bubble

There was a huge property and business boom but it all grew too big too fast, and after a point everyone started buying everything on credit. And in 1992, this crashed the entire economy, throwing the country into a recession that they still haven’t gotten out of. Pretty much what happened over here, just twenty years earlier.

So this is capitalism when it doesn’t work, which Miyazaki boils down to three factors:

- you take things you didn’t work for

- you have no respect for the resources you’re taking

- and you’re trying to solve problems by throwing money, or even worse, credit at it

Chihiro’s parents – the parable of doing capitalism wrong

This is what plays out in the first ten minutes of the film. The parents, who are not role models to begin with, disregard all social rules of how you behave in a Japanese restaurant, and want to pay for everything with credit.

But in this film you always see the effects of your actions almost immediately, you don’t have to wait seven years to see what happens.

With that in mind, here is Daddy Pig facing the realities of the credit-based market economy.

Eating as consumption in Spirited Away

So the parents are bad capitalism, but bad capitalism is quite an abstract thing, which is where eating comes in. And the visual is quite simple. In this film, you can look at eating as consumption.

So when you look at the instances of eating in the film, you can always look at the context and how that fits in with the idea of consumption.

Eating can be something you don’t want to do but have to do to survive. It might be the emotional release associated with comfort food. It might be a reward for work.

Bad capitalism #1 – losing your self to the company (literally)

Then there are the more abstract concepts around eating. Like how the company you work for can eat your name and claim ownership over your life – again the honne-tatemae question.

Bad capitalism #2 – consumption without concern for the environment

Then there’s the question of what you are feeding the environment, what are you giving your rivers to eat. There’s a fair amount of vomiting in the second half of the film. The bad things that went in have to come out.

Bad capitalism #3 – substituting objects for humanity

Another angle of capitalism that Miyazaki criticises is that we tend to substitute objects for human connection. People give gifts and sweets as a substitute of actually helping them to cope with an emotional crisis. You can give your baby all the toys in the world but not if you don’t let him out of the house, he’ll never grow up.

Bad capitalism #4 – substituting money for God

You can also adore money as a god but that only leads to a shallow one-dimensional existence where everything in your life will revolve around it. And you can be like No Face and struggle with making social connections. The poor thing deciphers that people react when you give them stuff, but then No Face is not really good at balancing giving and taking.

But Miyazaki’s not anti-capitalist

All this said, it’s important to note that this is not an anti-capitalist film. It’s not saying for one moment that capitalism itself is bad. Miyazaki is not a revisionist, he’s a progressive.

Good capitalism #1 – spiritual and material wealth can coexist

So he also shows how spirituality and material wealth can coexist, and how they do not contradict each other. Like how the river god leaves behind a magical object as well as gold in exchange for the service it was provided. (By the way, the exact same concept appeared previously in Castle in the Sky.)

Good capitalism #2 – objects can be imbued with humanity

Likewise, objects can be given by friends and can serve as a reminder of deeper truths. Having material things, like food or money, is not the problem. The problem is when you gain material wealth without service or through greed.

Good capitalism #3 – honest work is good

For Miyazaki, good capitalism is where everyone participates in serving society, and we all do something nice for each other.

Good capitalism #4 – capitalism works if everyone shares its benefits

So at the end of a good day’s work, you can all eat as a community, and you can share a meal, with everyone sitting at the same table, no matter who they are and what level of society they come from.

So much more to discuss in Spirited Away…

There’s so much to talk about with this film, and there are huge topics I didn’t even mention, like word magic, or the Shinto mythological origins for the characters, how the story flips Disney film storytelling rules, or that whole subplot with the name seal. Or all the easter eggs, like the shoutback to Totoro, or to Akira, or the Pixar lamp.

So these I will all do separately in other talks, if you want to learn about those you can sign up to my mailing list by grabbing the full Studio Ghibli guide:

Get the Studio Ghibli Secrets Guide!

Video credits

Written and performed by Adam Dobay

Additional research by Gabi Trost

Recorded by Livia Farkas

Editing by Gabi Trost and Eszter Vermes

Special thanks to Flick Beckett and the Duke of York’s cinema staff

Further reading

- Author and Bram Stoker Award nominee Thersa Matsuura dug up some awesome Japanese research on kamikakushi in her amazing podcast episode on the subject. Do give it a listen if you’re interested further in this very Japanese version of the “staying with the gods” trope. (For bonus brownie points you can compare and contrast the story she tells with what goes on in Spirited Away.)

- I was delighted to find that video essayist Margarita G has had a very similar take on the film recently, focusing on the loss of identity and she brings in a great take on the film’s portrayal on consumer culture from her background in psychology. If you’re interested in more about this side of the film, I recommend you check out her blog post on this.

Now it’s your turn!

What’s your biggest takeaway from this video? Is there something you’d like to hear more of? Let me know in the comments!

Hi Adam, I find your research pretty tip-top 🙂 You’ve helped me understand and navigate the layers and complexity of these films so much. The final ‘So much more to discuss..’ part stirs my curiosity. Ghibli films, especially Spirited Away and Howl’s have become increasingly important to me. Would absolutely love to hear you dissect them in more details.

Best,

Mai

Thank you! You will hear more – we have just recorded two episodes of the podcast going deeper into Spirited Away. I don’t have a release date yet as I have still more episodes to finish editing and uploading, but if you’re on the newsletter, you’ll get an email as soon as I’ve put it up 🙂

Hello Adam! I really enjoyed this article and its analysis about its symbolic and contextual themes. It’s really outlined some pretty major messages that bring out the richness and thought put into Spirited Away. Can’t wait to see more about film interpretations – thank you for doing what you do to highlight the interpretations we have on the films of the world, keep it up :D!

My appreciation for such a fantastic film has doubled yet again, thank you 🙂

Teri